Richard Reeves is Managing Director at the Association of Online Publishers (AOP), a UK industry body that represents digital publishing companies.

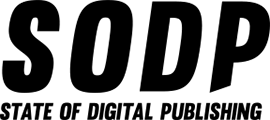

The death of the third-party cookie is supposed to benefit publishers, better positioning them to extract greater advertising value from their first-party data.

However, between preparing for the “cookieless future”, fighting Facebook and Google for compensation over news snippet sharing and trying to identify the emergent risks posed by AI, some publishers may not be aware of another potential issue on the horizon.

The UK-based Association of Online Publishers (AOP) printed an open letter in March warning the publishing and advertising industries of the dangers of content verification vendors’ unauthorized data scraping.

The letter, which was signed by AOP Managing Director Richard Reeves, argues these vendors — either through packing hidden tags into authorized in-header wrappers or using crawlers — are building “contextual audience segments for their own commercial gain”.

“Nefarious first-party data extraction amounts to theft of publishers’ intellectual property (IP), with negative impacts extending across publishers, advertisers, and agencies,” it states, before adding: “A commitment that the whole industry is united in addressing these concerns will help delay — and ideally prevent — more radical, disruptive publisher action.”

To better understand the AOP’s concerns and the potential dangers to publishers, State of Digital Publishing (SODP) reached out to Reeves with some questions. What follows is a lightly edited version of his response.

How will the collection of publisher metadata and article text pose a threat to the publishing community? Would better audience profiles not lead to more accurate contextual targeting and a more focused pool of buyers?

Digital publishers would be the first to agree that aligning advertising more closely with the content audiences choose to consume is positive. Most see the shift from behavioral to context-based targeting as an important part of building stronger user relationships and trust — and they recognise the potential of increasing buyer demand to drive higher CPMs.

The problem is they aren’t alone in looking to harness these benefits. Vendors have long been permitted to access publisher content for brand safety verification, but many are going beyond this limited purpose; using hidden tags to scrape data and build contextual audience segments for their own financial gain.

In addition to violating trust, this practice denies publishers the exclusive right they should hold to monetise their first-party assets, eating away at essential ad yield and the vital revenue it generates.

How does this practice undermine publishers’ ability to enrich user experiences and ad inventory? Can you expand on how it depletes publishers’ competitive advantage in generating ad revenue?

On paper, the decline of third-party cookies puts publishers in a strong position. As well as direct audience access, they have rich stores of data that should mean they’re uniquely well placed to support compliant, context-centric targeting and fuel higher revenues. The reality, however, is that with intermediaries muscling in, their offerings hold and generate less value.

To illustrate what I mean, let’s revisit an analogy I often use — an apple orchard with public byways.

Orchard owners put significant money, time and effort into cultivating their produce. While it may not be serious for one walker to pass through and steal an apple, there are major issues when large groups start arriving with big baskets, loading up and taking apples to market. The grower isn’t getting sufficient return on their investment, they can no longer promote goods as unique, and they might be undercut by sellers with almost zero margin to cover.

Publishers pour huge resources into producing quality content and cultivating close audience ties, while some have also invested heavily in ramping up their ability to create contextual segments and forge lucrative data sharing partnerships.

Like orchard owners, publishers’ capacity to capitalize on all this hard work is being eroded, which is especially tough at a time when revenue is under threat from economic turbulence. And the worst part is, publishers feel obliged to keep the gate open for vendors, because brand safety assessment is table stakes for programmatic buyers.

Which law does this process breach and how?

Some argue this issue falls within a gray area of the law, but the short answer is it amounts to theft of intellectual property. As such, I don’t consider it a gray area, but rather an example of the law — which, by design, moves slowly — not having caught up with the rapid pace of change in data technology. When it does catch up, questions will focus around who owns what asset, and who has the right to exploit these assets for commercial gain.

While article text is obviously an owned asset, the same status applies to data associated with publisher media and on-site, or in-app, interactions. This includes page titles, descriptions and keywords, alongside audience engagement factors, such as scroll speed and screen orientation. So, in plain and simple terms: collating and leveraging this data without first gaining consent is stealing from publishers.

Where there is no legal gray area whatsoever is in instances where vendors are breaching their contracts with publishers, many of whom explicitly limit the use of their data assets to non-commercial purposes in their terms and conditions. We are currently advising publishers to update their terms and conditions to protect their organizations from unauthorized data scraping.

How big an issue is this for buyers? Is there any data to suggest content verification vendors are misleading buyers?

Associating with unscrupulous vendors risks seriously damaging buyer reputations and consumer confidence, on top of casting a shadow on campaign integrity. As highlighted in our open letter, brands and agencies have limited transparency into data provenance, which means contextual ads might be running on unauthorized and unreliable data. My question to agencies is: Can you verify the data used to inform your campaigns has been collected legitimately?

The exact scale of the issue is hard to quantify — and primarily, for now at least, this is an issue of principles. Just because you can do something, doesn’t mean you should. In a multi-million-dollar space with hundreds of vendors, very few have reached out to discuss publisher compensation for data use.

Instead, several publicly listed companies tout extensive and precise publisher data mining as one of their chief strong points, with little-to-no mention of licensing. As a result, large numbers of buyers are in the dark about what data processes are happening under the surface.

How might buyers find themselves bearing more responsibility for data mishandling? Is this a legal concern?

Vendors at large are unsurprisingly tight lipped on this issue, but hints from those who have commented signal possible red flags for buyers. Specifically, the suggestion that vendors only extract publisher data at the request of buyers has the distinct air of passing the buck. While it’s too early to tell whether such blame shifting will extend to legal responsibilities, buyers need to start carefully considering this risk.

It’s also important to emphasize the potential for data quality issues to spiral rapidly if action isn’t taken soon. The more vendors are allowed to operate with seeming impunity, the more likely it is that we’ll see further growth in the number of contextual vendors deploying unauthorized crawlers. As contract holders, buyers have the power to prevent escalation and influence vendors by demanding clear proof of official licensing and permission to collect data. Time, however, is running short.

Does Trustworthy Accountability Group (TAG) membership mandate the use of the group’s Brand Safety Certification? Is there a system in place to address breaches?

Basic TAG membership does not require certification, though platinum membership does and any organization displaying a Brand Safety Certification seal must absolutely abide by its guidelines.

Content from our partners

The most recent update to these guidelines — effective January 1, 2023 — sets out clear definitions around publisher data applications and specifically differentiates between legitimate and illegitimate data use. TAG has confirmed organizations in breach of this new clause will not be certified.

In addition to TAG, the IAB Gold Standard requires Brand Safety Certification, adding another layer of accreditation that will be off-limits to vendors using publisher data outside of contracted terms.

As for enforcement, Brand Safety Certification is awarded on an annual basis. While I would of course want to see a faster pace of progress, this does add significant time pressure for any currently certified companies to ensure full compliance. If they are found to be in breach of the guidelines at their next audit, they will lose their certification. It’s going to be interesting to see how this is enforced, and who loses their seal, over the next 12 months.

Can you expand on the type of “radical, disruptive publisher action” that might be taken if the publishing industry’s concerns are not met?

It’s essential to first reiterate that disruption isn’t “Plan A”; our main hope is achieving resolution through collaboration. Other routes will only be considered if co-operation fails.

Publishers have a right to protect their IP and some may decide to do so via decisive action. What that looks like will vary, but as mentioned in the open letter, there are legal precedents for cases against companies using non-consented data, such as Getty Images vs Stability AI.

Publishers across the digital space, however, recognise this issue hasn’t yet been widely spotlighted, which is why our current goals are focused around raising awareness and encouraging constructive discussion.

All inhabitants of the ecosystem need to understand the negative effects of data misuse, and coming together is the best way of finding a mutually beneficial — and fair — path forward.