Across the country, academics, journalists and researchers are mapping their state’s news and information ecosystems.

Their methodologies differ, but such initiatives seek to make sense of the splintered reality of where people are getting their local news and information. Often, it’s not just from a legacy news organization such as a community newspaper, TV station or a notch on the radio dial.

Local news mapping in communities goes back more than a decade. But ever since researchers at the Center for Cooperative Media at Montclair State University created a first-of-its-kind interactive news map of New Jersey in 2020, similar projects have exploded.

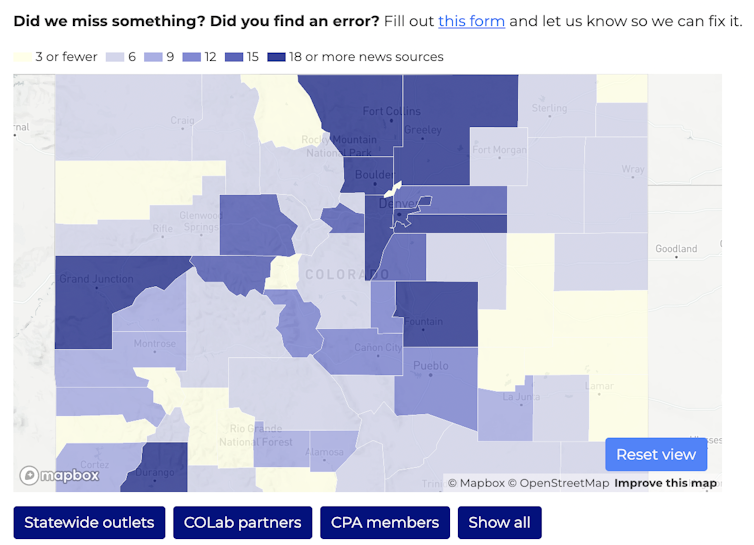

As an instructor at Colorado College where I manage the Journalism Institute, I’m borderline obsessed with the ways in which people get their local news and information. For a class called The Future and Sustainability of Local News, students and I have interviewed and surveyed Colorado residents about that. We created an interactive map that shows where Coloradans are learning about what’s going on in their communities in all 64 counties in the state.

We first published the Colorado news mapping project in 2022 in partnership with the University of Denver and others. It includes a growing list of 600-plus news and information sources. The map, which we update regularly, includes everything from podcasts and Facebook groups, TikTok and Instagram accounts, to Substack newsletters and more.

In one of our state’s least populous counties, San Juan, one student learned about “an individual community member going door-to-door to tell people about certain events or occurrences.” Yes, that modern-day town crier appears on our map.

A glance at the graphic shows which counties have plentiful sources of news and information and which ones don’t. It also includes census data about population and demographics.

Local news mapping projects take off

Colorado is one of several states with such projects.

Last year, universities charted the local news ecologies of Nebraska, Maryland and Minnesota. Around the same time, projects began for New Mexico, Montana, Wisconsin and Wyoming. They followed maps in Oregon and elsewhere.

Washington State University is creating a map with funding from a legislative effort to support local news. It might even inform how lawmakers there create public policy.

Researchers have also sought to assess the local news environments in specific regions, such as New England, southern New Mexico, California’s Inland Empire, and the cities of Philadelphia, Baltimore and Detroit.

A framework for mapping local news

Those of us doing this labor-intensive research are benefiting from organizations helping to make it easier.

Last year, the company Impact Architects published a news and information ecosystem playbook and accompanying workbook that helps researchers compare a community’s news and information ecosystem with others. Resources include how to set baselines and collect data.

These mapping and assessment initiatives come as local newspapers increasingly shrink or disappear from communities. Papers have vanished at a clip of roughly two per week, according to a study from Northwestern University’s State of Local News Project. Coupled with broader cuts in funding and staff, the development has led to what researchers call “ghost papers” and “news deserts.”

A 2023 landscape study of Georgia troublingly found that 17 of its counties do not have a single source of professional local news whatsoever.

Colorado’s methodology

To make sense of Colorado’s landscape, we used a loose methodology.

We chose not to be judge and jury on the legitimacy of a source. We added something to our map if residents told us they relied on it or if it had an otherwise demonstrable impact in the community. By doing so, we sought to reflect the reality of where people look for news and information in a county and what is available.

On our map, we noted whether a source was a member of a professional journalism organization and what kind of ownership structure it has. We included a brief description about each source for context.

University of Denver researchers Kareem Raouf El Damanhoury and David Coppini initially synthesized two public databases to get a baseline of outlets in each Colorado county. They also analyzed news coverage in each county on a single weekday in 2021 and gauged the number of original and local stories produced.

Colorado College students then interviewed people in the counties to identify more sources. We sent surveys to local news organizations to publish in their communities as well.

Calvin University journalism professor Jesse Holcomb has worked on and researched news mapping projects. He found a “main tension” is scale versus precision.

Scale, he said, allows researchers to make broad, generalizable assertions about the state of a landscape. But it can come at the cost of granular detail from “laborious, bespoke groundwork” at the community level.

“By contrast, research that prioritizes precision and accuracy is often limited to case studies, and thus it’s harder to make generalizable insights,” he said.

Those scaling up a news map might look for efficiencies in decision-making, such as identifying a news outlet by brick-and-mortar location instead of coverage area.

“The former is easy to measure but limited in what it actually tells you,” Holcomb said. “The latter is difficult to measure but yields more reward in terms of insight.”

An evolution in news mapping

Often housed in higher-ed journalism departments, this new breed of local news and information mapmakers are equipped with rapidly developing tech tools.

They are conducting the state-level news ecology research at a time when national and local philanthropic organizations raise and spend money to help revitalize the nation’s local news scenes.

Content from our partners

“It’s important for funders in our network to understand not only which geographical communities various newsrooms are reaching, but also the specific audiences that they are designed to serve – and how,” said Melissa Milios Davis, network manager for Press Forward, a nationwide philanthropic initiative. “Seeing all of this useful information in one place – even with layers of data on socioeconomic and civic engagement data – helps target philanthropic dollars in the communities and contexts that need it most.”

As these disparate state-based maps increasingly take shape, Sarah Stonbely from the Tow Center for Digital Journalism is building a national local news registry. It’s focused on all civic information providers. Think community centers, chambers of commerce, local governments and even small businesses.

Other initiatives, such as the Civic Information Index and the Roadmap for Local News, have advocated for similar approaches.

“Just as the local news landscape has evolved, so has local news mapping,” Stonbely said. “It has become clear that journalists are no longer the gatekeepers; there are now so many ways that people get news, especially in local journalism deserts. Our efforts to provide actionable data about local news landscapes have had to evolve accordingly.”

A local news map near you

As researchers map their own communities, they have support from those who have tread similar ground.

A group of academics at multiple universities have formed the Local News Impact Consortium, which collaborates with researchers and practitioners to help develop standards and protocols. Its goal is to “expand the rigorous study” of local information ecosystems across the country.

Later this year, the annual Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication conference is slated to include a panel dedicated to the topic: Mapping local news ecosystems and filling the gaps.

I plan to represent Colorado’s project on the panel. Who knows how different it might look by then.

Corey Hutchins, Manager, Colorado College Journalism Institute, Colorado College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.