Digital publisher advertising revenue has been in decline, particularly hard hit by the COVID-19 pandemic as advertisers began canceling accounts or drastically scaling back. Publishers have pivoted to other revenue models and made tweaks to their own ad monetisation strategies in response.

What history can teach us

Similar ad declines, and rushes to alliances occurred after the financial crisis of 2008-2009. Collaborations such as QuadrantOne in the U.S., consisting of The New York Times, Hearst, Gannett and Tribune Publishing, sought to pool ad inventory and monetise through programmatic. However, it was relatively short-lived, closing in 2013 after just five years.

In the U.K., Project Juno was an initiative formed by many leading newspaper companies including News UK, Trinity Mirror and Telegraph Media Group. However, it also ended in 2017 after publishers began pulling out one at a time.

What do these failed alliances tell us? Or is there simply a lifespan for such ventures that sometimes comes to its natural end? Some of these have ended amidst bickering or disagreements about how to run the networks, while others seem to have disbanded as member companies adopted new strategies.

AdExchanger offered some potential insight into these closed initiatives. “The disintegration could – in part – be attributed to growing internal programmatic strategies that create better yield than the assumed scale of the co-operative. Also, this may be a sign that exchanges are creating better yield these days. Why manage a separate exchange when you can go through existing exchanges such as Google’s DoubleClick Ad Exchange, PubMatic, Rubicon Project, AppNexus and so on, and receive comparable or better CPMs.”

The cookieless future

The GDPR impact is an important driver of a new move to programmatic ad networks and collaborations. WAN-IFRA called this a “seismic impact” in its new report, Publisher Ad Alliances – Why they make sense and how they work.

“It’s never been more important to share learnings and act together,” wrote Nick Tjaardstra, Director of Global Advisory, in the report’s foreword. “The big tech players can leverage the economies of scale that come with a global footprint, and take a strong negotiating position with national publishers.”

WAN-IFRA does not foresee a global ad alliance happening, but does predict cross-border and cross-industry alliances. The report focuses on five specific alliances, offering case studies and best practices.

New collaborations: Washington Post’s Zeus

Despite prior setbacks, 2020 brought signs that many publishers were looking to create new advertising alliances to boost the abysmal revenue post-COVID. The Washington Post is one of these, having developed a media monetization platform called Zeus Technology. The idea began in 2015, when the company was facing an existential crisis. Its content was being served via Facebook and Google — however, readers were consuming it via the platforms, with no reason to ever leave to visit the Post website itself, much less subscribe.

This is a challenge that most digital publishers face. The Post’s response was to build its own ecosystem that would rival that of the tech giants. Great technology is at the heart of this, which is where they feel that past alliances have failed. In order to truly capitalize on collective advertising power, powerful software has to be in place for both publishers and advertisers.

More than 100 websites have already signed up to be part of Zeus, including MediaNews Group, Tribune Publishing, McClatchy, the Seattle Times, the Dallas Morning News and Snopes.. Some of the major draws are its speed and publisher-focused strategy. It also renders ads, and the connection between bidding and rendering results in increased performance.

Mike Orren, chief product officer at Dallas Morning News, said, “They understand the news business vs. someone that is a pure tech player.”

Jarrod Dicker, VP of commercial tech at Washington Post, said the tech can help publishers improve viewability even if their rates are as high as 60% to 70%, without sacrificing impression volume, user experience or the ability to add additional demand sources.

Local Media Consortium

The Local Media Consortium is a Google-sponsored alliance of nearly 90 newspapers, broadcasters, and digital media. While its purpose is largely as a content-sharing platform, the members believe this initiative will help them compete with nationwide outlets for subscribers and advertising.

“This fight requires scale,” wrote Grzegorz Piechota at the International News Media Association. “More content to convert and engage subscribers, and more reach and inventory for advertisers.”

One of LMC’s initiatives is The Matchup, a sports content and ad sharing platform. A user subscribes to one of the member publications, and then gains access to articles published by other members without additional charge. The alliance allows them to compete at scale — put together, The Matchup members have a combined audience of 78 million unique visitors, the third largest behind ESPN and Yahoo.

The Dallas Morning News is also an LMC member, and Orren said that the main reasons he believes previous collaborations failed were publishers were seeking unique terms, over-complicated things, wanted a perfect model and focused exclusively on profit rather than other member benefits.

J-PAD

One of the most recent publisher coalitions was in Japan, when in October the Japan Publisher Alliance on Digital was launched. Six of the country’s premium publishers were founding members, including AFPBB News, Forbes JAPAN, JBpress, Mediagene, Perform Group and Toyo Keizai.

The Japanese digital advertising market has been expanding over the past several years, but the low CPMs (about one-third of the U.S.) indicate that digital advertising is still very much seen as a direct response mechanism. The establishment of premium publisher alliances such as J-PAD should create an environment for more ad budgets to be spent programmatically, thereby increasing their value and providing Japanese publishers with the higher returns that their global peers attract.

Creating successful publisher alliances

PubMatic, an SSP for agencies and advertisers, outlined some key factors that are needed for publisher ad alliances to be successful.

- Scale: For an alliance to be a success, and remain competitive, it needs to have significant audience reach – say, more than 60% of the online population – as this is what Google and Facebook will be offering.

- Brand safety: Alliances need to include respected brands that buyers want to target. Brand safety means publishers can control and restrict who has the privilege of accessing their inventory to help ensure that the quality of the ads on their sites matches their brand values and the quality of their content.

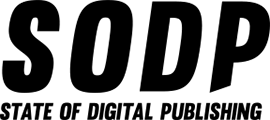

- Efficiency: Having a centrally-managed inventory pool means that any additional resources required will be shared between alliance members, or, in some cases, by the technology partners. There’s also the benefit of shared knowledge. For buyers, alliances provide the simplicity of a single bid enabling access to a large and appealing audience, with seamless allowlists, frequency capping, unified analytics and (ideally) shared and enriched audience data to target with.

- Leverage: Most publishers feel they are not being paid a fair market value for their content. If publishers can create scarcity through an alliance, they can charge buyers a higher price. Scarcity is key — if a publisher also makes their inventory available through other exchanges and ad networks, then the buyer’s incentive to pay more through the alliance is diminished.

- Shared vision: It’s important for companies in an alliance to define their shared goal and the path they plan to take to get there upfront. These can be as simple as revenue and yield goals, the types of sites allowed, how inventory is bundled, requirements for adding new publishers, and determining how the alliance will be governed. It’s important not to be too rigid, however, and to ensure these metrics allow for collaborative behaviour.

- Commitment and patience: Publishers with a wait-and-see attitude, that aren’t ready to commit fully, are not ideal partners. The decision to form an alliance should be a fundamental part of a publisher’s corporate strategy and, therefore, have a long-term view. Showing commitment is key, and all participants should signal their intent, either by guaranteeing large volumes of quality inventory, providing people, skills and expertise, or monetary investment such as marketing costs or management salaries.

- Structure: The two most obvious structures for an alliance are a joint venture or a strategic partnership, which may or may not be contractual. No single model will work in every situation, and determining the appropriate one depends on the situation and players involved.

- Technology partner: The success or failure of an alliance isn’t necessarily a question of the right technology, but of the right technology partner. This partner should have a global presence – ideally with a good reputation, must have sufficient integrations in the market in order to ensure maximum buyer participation, and should have multiple buying options such as OpenRTB, private marketplace (PMP), PMP-guaranteed and automated guaranteed across all channels and ad format. These are minimum requirements to ensure that buyers can buy how they choose to. A tech partner with a consultative approach that’s willing to dedicate resources, if necessary, that can also offer meaningful advice will be a true valued partner.

If publishers look to the past for lessons learned, look to current successful working alliances for modeling, and consider these key factors when building a new alliance, the rewards and long-term value can be substantial for both publishers and advertisers.