Jason Black is a Seattle area developmental editor of Plot to Punctuation; who helps authors from around the world improve their writing craft, story structures, and character development. Formerly, Jason has been a monthly columnist for Author Magazine, where he wrote a four-year column on character development, as well as for the literary journal Line Zero. These days, his efforts go toward his own blog of in-depth writing craft articles.

WHAT LED YOU TO START WORKING IN DIGITAL/MEDIA PUBLISHING?

I got my start as a developmental editor because people told me I was good at it, and I needed cash. I wish I could say there was some deep, philosophical motivation at the start of it, but the initial choice was entirely pragmatic.

After I wrote my first novel, my immediate question was whether it was any good. Friends and family would say, “Oh, yes, that was great,” but I couldn’t trust that they were being truly honest and not merely kind. So I started critique-swapping with other writers online, figuring that other writers could tell me what I needed to do. I desperately wanted feedback that would point me towards how I could write it better, structure it better, reveal character emotions better, and so forth. I worked hard to give other people the same kind of pointed, careful, actionable feedback I wanted. In my mind, feedback is useless if it doesn’t tell you specifically what you can do to address a problem.

Then a funny thing happened. Time and again, the writers I sent my work to respond with the same generic thumbs-up feedback that friends and family had given me. That was validating, to be sure, but didn’t teach me anything about the craft. As well, time and again people came back to me to thank me for the specific guidance I’d given them. More than once, people told me, “that feedback was so helpful, you could charge money for it!”

So, when the recession came in 2009 and I found myself unexpectedly unemployed, I decided to do exactly that and started my freelance developmental editing business. It feels good, knowing I have a skill people value and that seems to be something of a rare trait.

WHAT DOES A TYPICAL DAY LOOK LIKE FOR YOU?

Much as I wish this were a 9-to-5 affair for me, the realities of health care in America dictate that I maintain a day job as well. But, since I work as a technical writer in the software industry, at least my days are devoted to work that hones my own writing and editing skills. From 5 to 8, give or take, is dinner and family time. The late evening hours of 8 to 11 are my editing time. It’s a busy lifestyle, but I do enjoy the work.

WHAT’S YOUR WORK SETUP LOOK LIKE?

Nothing particularly special. My main tools are Microsoft Word and Excel, running on an ordinary Windows laptop. Word is an obvious pick, being the de-facto standard in the publishing industry for manuscripts, and also has very robust editing and commenting features which are essential when marking up a client’s manuscript. Excel is fabulous for tracking my client projects, schedule, and time spent on each project.

The only piece of equipment I can’t live without is the external monitor connected to my laptop. Between marking up and commenting in clients’ manuscripts, and making notes in the reports I generate for my clients, I simply can’t get by without a lot of screen real-estate, and laptops these days just don’t have screens that are big enough. I use a big, 1920×1200 resolution monitor that allows me to have two full Word documents, side by side, at 100% zoom. Being able to see and work with both documents simultaneously makes a world of difference in my productivity.

WHAT DO YOU DO OR GO TO GET INSPIRED?

Stay receptive. Keep my filters open.

Maybe that sounds new-agey, but it’s really true. When it comes to my own writing, inspiration always comes from the world around me. I once got an idea for a novel from a wisecrack somebody on twitter made about a spammer. Inspiration can come from anywhere; the writer’s job is to be receptive to it, even when it comes from an unexpected source.

For my client projects, inspiration comes in the form of the pleasure I take in teaching. I don’t think someone can be a good developmental editor if they don’t like to teach, because 90% of the job is not in identifying what the client needs to do to their story, but in teaching them the skills to do it. So, when I see a client writing a particularly juicy example of some writing craft issue, I quite enjoy deconstructing the example so as to show the client what the issue is and how to address it, within the context of their own work.

As well, every manuscript teaches me something new about writing. Every single one. Without fail. Remember when I said that no feedback is worth anything if it doesn’t also help you address a problem? That philosophy means that when I stumble across a word, a phrase, a paragraph, or a plot development that doesn’t feel right, I can’t just say “this part was no good.” That wouldn’t help the client. Instead, I have to think very carefully about why it feels wrong. Identify the underlying issue. Figure out the pattern of it, and how it can be fixed.

After eight and a half years of doing this, most of the time I know what the issue is right away. Nevertheless, every manuscript still manages to surprise me at least once with something new. Something I haven’t seen. Something for which I don’t have a ready-made answer in my pocket. Then I get excited, because I know it means I’m about to learn something new about writing too.

WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE PIECE OF WRITING OR QUOTE?

Lately, it’s this Martin Luther King, Jr. quote:

“Everything we see is a shadow cast by that which we do not see.”

I love that because it is such an eloquent expression of the core idea behind “show, don’t tell,” which is itself the core technique of narrative writing. King knew that the most important things in our world are that which we do not see: other people’s hopes, dreams, fears, loves, prejudices, motivations, beliefs, feelings, and values. For it is those things, locked up beyond sight inside the heads of other people, which shape our experience as human beings.

And yet, though invisible, those things reveal themselves through the shadows they cast into the world. People’s words, their actions, their inactions, and even their body language reveals–if we choose to see it–everything that matters to them.

When conveying their stories, writers have two options. They can tell the reader directly about each character’s invisible feelings. Or they can show the reader the shadows, and leave it to the reader to intuitively understand the most important things in the story.

WHAT IS THE PASSIONATE PROBLEM YOU ARE TACKLING AT THE MOMENT?

It’s always the same: doing the best possible job I can for my current client is. Every manuscript is a unique challenge, and while they certainly show patterns, each one is its own mix of strengths and weaknesses. The challenge is always to read past what’s on the page to see what the client’s goals are in writing the novel–why that story? Why those characters? Why that particularly conflict or obstacle? If I can figure those things out, then I can see what the writer is trying to say with the novel, and can advise them on the big-picture view of their story and what they might alter to better-fit their vision.

IS THERE A PRODUCT, SOLUTION OR TOOL THAT MAKES YOU THINK IT IS A GOOD DESIGN FOR YOUR DIGITAL PUBLISHING EFFORTS?

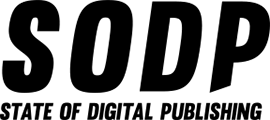

Content from our partners

As an editor, I’m satisfied with the tools at my disposal.

But as a would-be independent author, I’m not. I’ve watched the publishing landscape transform over the past decade from a world where traditional publishing was everything, to one where traditional publishing now competes head-to-head with self-publishing, but where the existing structural realities around book promotion, distribution, and sales are still stacked heavily in favor of traditional publishing.

I’ve watched as authors have tried–some successfully, some not–to build business models around Kickstarter, GoFundMe, and lately, Patreon. Each of these has its appeal, but all fall short for novelists, whose content creation model (high-effort, infrequent releases) is not well suited to the design of those platforms.

What indie authors need is something like Patreon, but geared towards the unique demands of novel-writing. Something that brings authors and audiences together in a symbiotic way around the act of creating novels. Why shouldn’t, for example, an author be able to write briefs for the story ideas on their to-be-written list (we all have one), and let the audience vote with their dollars for what they’ll write next?

That’s the digital publishing solution I’m waiting for.

ANY ADVICE FOR AMBITIOUS DIGITAL PUBLISHING AND MEDIA PROFESSIONALS JUST STARTING OUT?

Be humble, and listen more than you speak.

For writers, especially, I know how tempting it is, after banging out a novel, to shove it as fast as you can through CreateSpace’s print-on-demand pipeline. Presto! You’re an author!

But don’t. Take your time. Do your homework. Learn what’s involved in putting a quality, professional product you can be proud of and that can hold its own on a bookshelf next to anything from the big-six publishers. Learn about all the different kinds of editing, from developmental editing on down. Learn about book cover design. Learn about typography and typesetting. Learn about book design. And find freelancers who can help you with all of that. We’re out there, waiting to take those burdens off your shoulders so you can spend your time writing more books.